Chapter One

Highlights of Eritrean

History

her hands unto God

Psalm 68:31

![]() Eritrea,

as a geographical and political entity, is a scant eighty years old, yet the

history of the tribesmen who populated the northern highlands antedates the

erection of Stonehenge in England. Owing to the geographical location astride

pilgrimage and trade routes, Eritrean history is suffused with foreign

influences ranging from Syrian Christianity to the culture of Arabian

immigrants. Even the name is foreign and is probably a derivative of the

ancient Greek cartographical designation, Mare Erythraean (Red Sea). But

foreign influence played a somewhat less beneficient role in Abyssinian

development. Historically, Eritrea was victimized by an endless succession of

invaders serving various causes. Pillage and barbarity were commonplace.

Moreover, social upheaval was the leit motif of Eritrean life for 3,000

years--a chronicle of invasion, religious contention, internecine war and

repeated instances of cultural assimilation. It was a society that pivoted on

military balances where only the strongest survived to dictate policy.

Eritrea,

as a geographical and political entity, is a scant eighty years old, yet the

history of the tribesmen who populated the northern highlands antedates the

erection of Stonehenge in England. Owing to the geographical location astride

pilgrimage and trade routes, Eritrean history is suffused with foreign

influences ranging from Syrian Christianity to the culture of Arabian

immigrants. Even the name is foreign and is probably a derivative of the

ancient Greek cartographical designation, Mare Erythraean (Red Sea). But

foreign influence played a somewhat less beneficient role in Abyssinian

development. Historically, Eritrea was victimized by an endless succession of

invaders serving various causes. Pillage and barbarity were commonplace.

Moreover, social upheaval was the leit motif of Eritrean life for 3,000

years--a chronicle of invasion, religious contention, internecine war and

repeated instances of cultural assimilation. It was a society that pivoted on

military balances where only the strongest survived to dictate policy.

![]() Present

day Eritrea comprises an area roughly equivalent to the state of New York. It

is a land of fascinating topographical extremes. Mountainous highlands bisect

the area with elevations up to 8,000 feet, broad ambas of rocky

grassland and a pleasantly temperate climate. To the west, the sparsely

vegetated lowlands marry the Sudanese deserts, and on the east, the coastal

plains merge with the Great Rift Valley in the Danakil Depression, reputed to

be the hottest place on earth. The geography, particularly the precipitous

escarpments, has also been a contributing factor in Eritrean history. The

ascents from the peripheral lowlands have historically provided a formidable

barrier. For much of its 3,000 year history, the security of the highlands

allowed the Abyssinian culture to metamorphose with minimal foreign

infringement. Even though Europe had been aware of Abyssinia's existence since

before the birth of Christ, the first Europeans didn't arrive until well into

the Middle Ages.

Present

day Eritrea comprises an area roughly equivalent to the state of New York. It

is a land of fascinating topographical extremes. Mountainous highlands bisect

the area with elevations up to 8,000 feet, broad ambas of rocky

grassland and a pleasantly temperate climate. To the west, the sparsely

vegetated lowlands marry the Sudanese deserts, and on the east, the coastal

plains merge with the Great Rift Valley in the Danakil Depression, reputed to

be the hottest place on earth. The geography, particularly the precipitous

escarpments, has also been a contributing factor in Eritrean history. The

ascents from the peripheral lowlands have historically provided a formidable

barrier. For much of its 3,000 year history, the security of the highlands

allowed the Abyssinian culture to metamorphose with minimal foreign

infringement. Even though Europe had been aware of Abyssinia's existence since

before the birth of Christ, the first Europeans didn't arrive until well into

the Middle Ages.

![]() The

question of the exact origins of the Eritrean people is still an academic one

although it is likely that early migrations into the Eritrean highlands

originated from the Kingdom of Cush. Cushitic kings dominated portions of

present day Egypt, Sudan, Ethiopia and Uganda about 700 B.C. The Cushitic

people who migrated into Eritrea during the first millennium B.C. were

primitive animists. At roughly the same time, the Semitic tribes of

southwestern Arabia had gained preeminence in the Near East, mostly as a result

of their successes in irrigated agriculture. When the Semites sought to

increase their demesne, the natural move was across the short expanse of the

Mare Erythraean in to Eritrea.

The

question of the exact origins of the Eritrean people is still an academic one

although it is likely that early migrations into the Eritrean highlands

originated from the Kingdom of Cush. Cushitic kings dominated portions of

present day Egypt, Sudan, Ethiopia and Uganda about 700 B.C. The Cushitic

people who migrated into Eritrea during the first millennium B.C. were

primitive animists. At roughly the same time, the Semitic tribes of

southwestern Arabia had gained preeminence in the Near East, mostly as a result

of their successes in irrigated agriculture. When the Semites sought to

increase their demesne, the natural move was across the short expanse of the

Mare Erythraean in to Eritrea.

![]() The

initial Semitic migrants found the arid coastal regions inhospitable and

gradually moved into the highlands and a terrain and climate akin to their own.

It was in the highlands that they first encountered the Cushitic tribes. After

a few hundred years of cultural interface, the Cushites were either absorbed or

driven south into the Danakil. The superior culture carried by the Arabian

Semites not only quickly assimilated the Cushites, but provided the foundation

on which the Axumite Empire was built. The early Semitic settlements became

important centers of trade by maintaining ties with Arabia and by taking

advantage of the bustling Red Sea commerce.

The

initial Semitic migrants found the arid coastal regions inhospitable and

gradually moved into the highlands and a terrain and climate akin to their own.

It was in the highlands that they first encountered the Cushitic tribes. After

a few hundred years of cultural interface, the Cushites were either absorbed or

driven south into the Danakil. The superior culture carried by the Arabian

Semites not only quickly assimilated the Cushites, but provided the foundation

on which the Axumite Empire was built. The early Semitic settlements became

important centers of trade by maintaining ties with Arabia and by taking

advantage of the bustling Red Sea commerce.

Although many stelae are found throughout Tigre and Eritrea, Axum's are the most imposing. They stand in prominent testimony of the Semitic culture transplanted in the Ethiopia highlands. Photo: Mike Hoffman |

![]() The

Axumite Kingdom gained prominence in the first century A.D. The exact

dimensions of the empire are not know, but there is evidence that it reached

north to the Nile Valley, east to Mecca and accounted for substantial territory

in Africa. Owing to its place as a center of commerce for the Red Sea, the

Axumite rulers were in contact with the Byzantine Empire and most eastern

Mediterranean countries. Ezana, the greatest of the Axumite kings (4th century

A.D.) is believed to have introduced Geez as the official language, but more

importantly, he was instrumental in making Christianity the official religion

of the kingdom.

The

Axumite Kingdom gained prominence in the first century A.D. The exact

dimensions of the empire are not know, but there is evidence that it reached

north to the Nile Valley, east to Mecca and accounted for substantial territory

in Africa. Owing to its place as a center of commerce for the Red Sea, the

Axumite rulers were in contact with the Byzantine Empire and most eastern

Mediterranean countries. Ezana, the greatest of the Axumite kings (4th century

A.D.) is believed to have introduced Geez as the official language, but more

importantly, he was instrumental in making Christianity the official religion

of the kingdom.

![]() During

the reign of Ezana's father, two Syrians, Aedesius and Frumentius, were

shipwrecked on the Red Sea coast. They were taken to Axum and eventually became

tutors of young Ezana. Since both Syrians were Christian, Ezana was evidently

schooled in Christian precepts. After Ezana became king, Frumentious and

Aedesius left Axum. Aedesius returned to Syria and Frumentius travelled to

Alexandria where he urged the Coptic Patriarch to send a bishop to preside over

Axum's nascent Christianity. Frumentious himself was consecrated sometime

around 340 A.D. and returned as the first Bishop of Axum. Upon his return, he

succeeded in converting his erstwhile student and Christianity began to spread

with royal endorsement. The conversion of the empire, however, was neither

immediate nor all-encompassing. Adherents to Judaism (Semites were Judaic) and

to paganism clung tenaciously to their beliefs and do to this day.

During

the reign of Ezana's father, two Syrians, Aedesius and Frumentius, were

shipwrecked on the Red Sea coast. They were taken to Axum and eventually became

tutors of young Ezana. Since both Syrians were Christian, Ezana was evidently

schooled in Christian precepts. After Ezana became king, Frumentious and

Aedesius left Axum. Aedesius returned to Syria and Frumentius travelled to

Alexandria where he urged the Coptic Patriarch to send a bishop to preside over

Axum's nascent Christianity. Frumentious himself was consecrated sometime

around 340 A.D. and returned as the first Bishop of Axum. Upon his return, he

succeeded in converting his erstwhile student and Christianity began to spread

with royal endorsement. The conversion of the empire, however, was neither

immediate nor all-encompassing. Adherents to Judaism (Semites were Judaic) and

to paganism clung tenaciously to their beliefs and do to this day.

![]() If

regionalism and civil war were the most devisive factors in Ethiopian history,

then it is Christianity that has been the unifying bond that has saved the

country from piecemeal conquest. Its historical significance cannot be

overstated. The solidarity of Christian Ethiopia has surmounted the

debilitation of inter-tribal war and numerous incursions of hostile

«infidels».

If

regionalism and civil war were the most devisive factors in Ethiopian history,

then it is Christianity that has been the unifying bond that has saved the

country from piecemeal conquest. Its historical significance cannot be

overstated. The solidarity of Christian Ethiopia has surmounted the

debilitation of inter-tribal war and numerous incursions of hostile

«infidels».

The Afars are direct descendents of the aboriginal Cushitic tribesmen who were driven into the lowlands by the Semities. Photo: Nancy Rasmuson |

![]() In the

early years of the 8th century, the loss of Axum's principal port to Muslim

invader sounded the death knell for the trade-oriented kingdom. Within a

century, the Eritrean seacoast and the Dahlak Islands were in Arab hands, and a

great portion of the lowland people (Cushitic) had become perforce adherents of

Islam. At the close of the 10th century, a pagan tribe led by a woman called

Judith invaded the northern highlands bent on the destruction of the last

vestiges of Axumite political power and the obliteration of Christianity.

Judith and her armies sacked churches and monasteries and butchered every

available Christian. (To this day, women are not allowed to enter St. Mary's

Church because of Judith's spoliation of Axum's old churches.) The upshot was

the loss of all northern regions and a fragmented government which retreated to

the south. From that point, the resultant ascendancy of Amhara authority in

southern Ethiopia occurred without any interface with the Eritreans who held

sway over the north. This separation certainly contributed to the acrimony

which came to characterize Ethio-Eritrean relations. It also served as the

foundation for the cultural barrier between the Amhara and Tigre tribes.

Judith's massacres may have also contributed to the rise of Muslim faith or the

Axumite peripheries, since there was something to be said for being a live

Muslim rather than a dead Christian.

In the

early years of the 8th century, the loss of Axum's principal port to Muslim

invader sounded the death knell for the trade-oriented kingdom. Within a

century, the Eritrean seacoast and the Dahlak Islands were in Arab hands, and a

great portion of the lowland people (Cushitic) had become perforce adherents of

Islam. At the close of the 10th century, a pagan tribe led by a woman called

Judith invaded the northern highlands bent on the destruction of the last

vestiges of Axumite political power and the obliteration of Christianity.

Judith and her armies sacked churches and monasteries and butchered every

available Christian. (To this day, women are not allowed to enter St. Mary's

Church because of Judith's spoliation of Axum's old churches.) The upshot was

the loss of all northern regions and a fragmented government which retreated to

the south. From that point, the resultant ascendancy of Amhara authority in

southern Ethiopia occurred without any interface with the Eritreans who held

sway over the north. This separation certainly contributed to the acrimony

which came to characterize Ethio-Eritrean relations. It also served as the

foundation for the cultural barrier between the Amhara and Tigre tribes.

Judith's massacres may have also contributed to the rise of Muslim faith or the

Axumite peripheries, since there was something to be said for being a live

Muslim rather than a dead Christian.

![]() The Zagwe

Dynasty (about 1148 to 1277 A.D.) was the next historically significant

development for Christian Ethiopia. The Zagwe sprung from Cushitic origins and

traced their lineage to Moses rather than to Solomon as the Axumite kings had

done. Because of this, succeeding emperors have denounced them as usurpers.

Most notable of the Zagwe kings was Lalibela who was the architect of the

monolithic churches in the present day Wollo village which bears his name. With

pilgrimage routes to the Holy Land interdicted by inimical Muslims, the 11

churches served as a new Jerusalem (replete with River Jordan) for Ethiopian

pilgrimages.

The Zagwe

Dynasty (about 1148 to 1277 A.D.) was the next historically significant

development for Christian Ethiopia. The Zagwe sprung from Cushitic origins and

traced their lineage to Moses rather than to Solomon as the Axumite kings had

done. Because of this, succeeding emperors have denounced them as usurpers.

Most notable of the Zagwe kings was Lalibela who was the architect of the

monolithic churches in the present day Wollo village which bears his name. With

pilgrimage routes to the Holy Land interdicted by inimical Muslims, the 11

churches served as a new Jerusalem (replete with River Jordan) for Ethiopian

pilgrimages.

The churches at Lalibela were painstakingly sculpted from solid rock. Legend has it that the process took 5,000 workers 25 years. |

![]() With the

end of the Zagwe Dynasty, the Solomonic line was restored and the political

center of the state became the Shoa (Amhara) region. This particular time in

Ethiopian development was highlighted by two events: the climax of the struggle

with the ever-encroaching Muslims and the first relations with Europe.

With the

end of the Zagwe Dynasty, the Solomonic line was restored and the political

center of the state became the Shoa (Amhara) region. This particular time in

Ethiopian development was highlighted by two events: the climax of the struggle

with the ever-encroaching Muslims and the first relations with Europe.

![]() The new

emperor was faced with the threat of Muslim encirclement and European powers

were equally uneasy over the threat to southern Europe posed by the

militaristic Muslims. They were also aware, in a vague sort of way, of the

presence of Ethiopia on the Horn of Africa as a potential Christian ally. Homer

(prior to 700 B.C.) and Aeschylus (525-456 B.C.) refer to Ethiopia in their

writings. Marco Polo (1254-1324) reported on a visit to Adulis on his return

from the Far East, and in general, Christian Europe was intrigued by the

Christian Red Sea realm they believed (or hoped) was ruled by the legendary

Prester John. Ethiopian delegates at the Council of Florence in 1441 galvanized

European interest and set the stage for a Portuguese-Ethiopian alliance a

century later. Since the Portuguese were the first to sail a fleet into the

Indian Ocean, they became the first Europeans to ally themselves with Ethiopia

in the continuing battle with the Muslims.

The new

emperor was faced with the threat of Muslim encirclement and European powers

were equally uneasy over the threat to southern Europe posed by the

militaristic Muslims. They were also aware, in a vague sort of way, of the

presence of Ethiopia on the Horn of Africa as a potential Christian ally. Homer

(prior to 700 B.C.) and Aeschylus (525-456 B.C.) refer to Ethiopia in their

writings. Marco Polo (1254-1324) reported on a visit to Adulis on his return

from the Far East, and in general, Christian Europe was intrigued by the

Christian Red Sea realm they believed (or hoped) was ruled by the legendary

Prester John. Ethiopian delegates at the Council of Florence in 1441 galvanized

European interest and set the stage for a Portuguese-Ethiopian alliance a

century later. Since the Portuguese were the first to sail a fleet into the

Indian Ocean, they became the first Europeans to ally themselves with Ethiopia

in the continuing battle with the Muslims.

![]() In 1516,

the Turks conquered Egypt and gained control of the ports on the Red Sea, and a

settlement on the Dahlak Islands flourished as a major slave trading center. In

1531, Ahmed Gran led a Muslim army of Somalis and Danakils in a bold attack

aimed at extirpating Christianity in the highlands. He overwhelmed Shoan forces

and pushed northward toward Tigre and Eritrea. In his wake he left gutted

churches and Moslemized Christians. Eleventh-hour salvation came from Portugal

who answered a long standing request for assistance by landing 400 troops in

Massawa. This Portuguese expeditionary force and the combined Tigre-Shoan

armies succeeded in defeating Gran. In the last major battle near Lake Tana,

Ahmed Gran was killed along with half of the Portuguese soldiers. The remaining

Portuguese stayed on and were assimilated into the population. After that

victory, the Muslim threat ebbed, although the Turks again seized Massawa

around 1560 and held fast for 300 years.

In 1516,

the Turks conquered Egypt and gained control of the ports on the Red Sea, and a

settlement on the Dahlak Islands flourished as a major slave trading center. In

1531, Ahmed Gran led a Muslim army of Somalis and Danakils in a bold attack

aimed at extirpating Christianity in the highlands. He overwhelmed Shoan forces

and pushed northward toward Tigre and Eritrea. In his wake he left gutted

churches and Moslemized Christians. Eleventh-hour salvation came from Portugal

who answered a long standing request for assistance by landing 400 troops in

Massawa. This Portuguese expeditionary force and the combined Tigre-Shoan

armies succeeded in defeating Gran. In the last major battle near Lake Tana,

Ahmed Gran was killed along with half of the Portuguese soldiers. The remaining

Portuguese stayed on and were assimilated into the population. After that

victory, the Muslim threat ebbed, although the Turks again seized Massawa

around 1560 and held fast for 300 years.

![]() The

primary motive for Portuguese intervention in Eritrea was the desire to convert

the citizenry to Catholicism. At the outset, the Portuguese missionaries

enjoyed some success, but eventual rivalries between the members of the

Catholic church and members of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church became so bloody

that all missionaries were expelled. This tumultuous period of civil and

religious strife contributed to a pervasive antipathy to foreign Christians,

and to xenophobia in general, that continued well into the 19th century.

The

primary motive for Portuguese intervention in Eritrea was the desire to convert

the citizenry to Catholicism. At the outset, the Portuguese missionaries

enjoyed some success, but eventual rivalries between the members of the

Catholic church and members of the Ethiopian Orthodox Church became so bloody

that all missionaries were expelled. This tumultuous period of civil and

religious strife contributed to a pervasive antipathy to foreign Christians,

and to xenophobia in general, that continued well into the 19th century.

![]() Changes

in political climate in Ethiopia in the early 17th century came to have a

significant impact on Eritrea. Emperor Basilides moved the permanent capital to

Gondar, thereby moving Ethiopian authority closer to Eritrea than it had been

since Axumite times. The precedent was set of rewarding Eritreans for loyalty

to the throne and vigilance against the Turks with parcels of land which

resulted in a new class of landowner. This echelon served as a catalyst for

Amhara influence in Eritrea.

Changes

in political climate in Ethiopia in the early 17th century came to have a

significant impact on Eritrea. Emperor Basilides moved the permanent capital to

Gondar, thereby moving Ethiopian authority closer to Eritrea than it had been

since Axumite times. The precedent was set of rewarding Eritreans for loyalty

to the throne and vigilance against the Turks with parcels of land which

resulted in a new class of landowner. This echelon served as a catalyst for

Amhara influence in Eritrea.

![]() In 1853,

an Egyptian army attacked and occupied Keren. Ethiopian alarm was shared to a

great extent by European powers who were wary of Egypt's designs on what had

become a strategically important area. The Turks had previously leased the

Massawa coastline to Egypt and throughout the Red Sea area. Egyptian presence

became increasingly apparent. Ethiopian and Egyptian settlements traded

hostilities regularly. European activity, in general, in the coastal regions

also increased. Following the French, the British consulate in Massawa opened

in 1849, and Italian missionaries settled in Keren.

In 1853,

an Egyptian army attacked and occupied Keren. Ethiopian alarm was shared to a

great extent by European powers who were wary of Egypt's designs on what had

become a strategically important area. The Turks had previously leased the

Massawa coastline to Egypt and throughout the Red Sea area. Egyptian presence

became increasingly apparent. Ethiopian and Egyptian settlements traded

hostilities regularly. European activity, in general, in the coastal regions

also increased. Following the French, the British consulate in Massawa opened

in 1849, and Italian missionaries settled in Keren.

About the same time that slaves first arrived at Jamestown, Emperor Basilides busied himself with castle construction at Ethiopia's first permanent capital--Gondar. |

![]() In 1875,

Egypt attacked Ethiopia from three sides. Although Egyptian forces succeeded in

occupying Harrar (where they remained for 10 years), Emperor Yohannes' armies

defeated them near Adi Quala. A second Egyptian army, led by an American

officer, landed at Massawa in December, 1875 and marched to Gura only to be

routed again. After the Battle of Gura, the Egyptians attempted no further

inland expansion and confined themselves to the coastal regions. Rather than

pressing the war into the peripheral lowlands, Yohannes concerned himself with

affairs in the highlands, but the interbellum tranquility was short-lived.

In 1875,

Egypt attacked Ethiopia from three sides. Although Egyptian forces succeeded in

occupying Harrar (where they remained for 10 years), Emperor Yohannes' armies

defeated them near Adi Quala. A second Egyptian army, led by an American

officer, landed at Massawa in December, 1875 and marched to Gura only to be

routed again. After the Battle of Gura, the Egyptians attempted no further

inland expansion and confined themselves to the coastal regions. Rather than

pressing the war into the peripheral lowlands, Yohannes concerned himself with

affairs in the highlands, but the interbellum tranquility was short-lived.

![]() In May,

1881, Sudanese Mahdists declared a holy war on all foreigners and overthrew the

Egyptian government. By 1884, Chinese Gordon was besieged (and later murdered)

in Khartoum, and Egyptian fortresses along the Sudanese coast were under

attack. The British, acting in a protectoral role, solicited Yohannes' aid in

evacuating the beleaguered garrisons in the Sudanese hinterland. Yohannes

complied and succeeded in evacuating forces from Kassala and Gallabat. These

towns were later re-captured by Sudanese Dervishes who then posed a very real

threat to the Eritrean lowlands and burned Gondar in 1887. In the face of the

threat, many of the lowland tribes sought the protection of the Italians who

had lately arrived in Massawa.

In May,

1881, Sudanese Mahdists declared a holy war on all foreigners and overthrew the

Egyptian government. By 1884, Chinese Gordon was besieged (and later murdered)

in Khartoum, and Egyptian fortresses along the Sudanese coast were under

attack. The British, acting in a protectoral role, solicited Yohannes' aid in

evacuating the beleaguered garrisons in the Sudanese hinterland. Yohannes

complied and succeeded in evacuating forces from Kassala and Gallabat. These

towns were later re-captured by Sudanese Dervishes who then posed a very real

threat to the Eritrean lowlands and burned Gondar in 1887. In the face of the

threat, many of the lowland tribes sought the protection of the Italians who

had lately arrived in Massawa.

![]() Italy was

on the coattails of the colonialist scramble for Africa in 1882. The completion

of the Suez Canal in 1869 had given the Red Sea littoral a strategic importance

upon which France and England had already capitalized in Djibouti, and Aden and

Egypt, respectively. The Italian missionaries who had been in Eritrea since the

1850's assumed a political role by urging the Italian Government to take

advantage of Eritrea's colonial potential. The Italian government took over

Assab from an Italian shipping company which had purchased it from an Egyptian

sultan in 1869. The main interest was not the port, but rather, the Ethiopian

interior. The hazards to travel posed by the hostile Danakil tribes prompted

the deployment of Italian troops in 1885.

Italy was

on the coattails of the colonialist scramble for Africa in 1882. The completion

of the Suez Canal in 1869 had given the Red Sea littoral a strategic importance

upon which France and England had already capitalized in Djibouti, and Aden and

Egypt, respectively. The Italian missionaries who had been in Eritrea since the

1850's assumed a political role by urging the Italian Government to take

advantage of Eritrea's colonial potential. The Italian government took over

Assab from an Italian shipping company which had purchased it from an Egyptian

sultan in 1869. The main interest was not the port, but rather, the Ethiopian

interior. The hazards to travel posed by the hostile Danakil tribes prompted

the deployment of Italian troops in 1885.

![]() The

aftermath of the Mahdist uprising found Italy in an active diplomatic campaign

to acquire some of the former Egyptian coastal holdings. The British encouraged

the Italians and in fact, turned over control of the port of Massawa. On

February 5, 1885, an Italian squadron arrived in Massawa, and by November, the

Italians were in complete command and actively recruiting Eritreans to serve in

their army. The majority of the lowlanders was only to anxious to enlist. The

primary incentive was protection from the marauding Dervishes. Within a short

period of time, Italian forces moved inland and occupied the lowland village of

Saati.

The

aftermath of the Mahdist uprising found Italy in an active diplomatic campaign

to acquire some of the former Egyptian coastal holdings. The British encouraged

the Italians and in fact, turned over control of the port of Massawa. On

February 5, 1885, an Italian squadron arrived in Massawa, and by November, the

Italians were in complete command and actively recruiting Eritreans to serve in

their army. The majority of the lowlanders was only to anxious to enlist. The

primary incentive was protection from the marauding Dervishes. Within a short

period of time, Italian forces moved inland and occupied the lowland village of

Saati.

![]() Emperor

Yohannes was truculent over British diplomatic policy and the subsequent

Italian encroachment. He dispatched an army under Ras Alula, architect of the

victories at Adi Quala and Gura, to stall the expansion. The army laid siege to

the Italian garrison at Saati and massacred a relief battalion marching across

the flats. The Italians raised a diplomatic hue and cry, but in the end,

retreated to Massawa.

Emperor

Yohannes was truculent over British diplomatic policy and the subsequent

Italian encroachment. He dispatched an army under Ras Alula, architect of the

victories at Adi Quala and Gura, to stall the expansion. The army laid siege to

the Italian garrison at Saati and massacred a relief battalion marching across

the flats. The Italians raised a diplomatic hue and cry, but in the end,

retreated to Massawa.

![]() In 1888,

the reinforced Italians reoccupied Saati, constructed a railroad to ferry

supplies from Massawa and fortified the town. Yohannes responded with 80,000

troops and a demand for immediate withdrawal. The Italians, however, held firm

and issued conterdemands which included Ailet, Ghinda and control of the

lowlands. The two armies remained poised on the brink of battle for several

weeks until Yohannes was obliged once again to withdraw to deal with the

Dervishes. Being a devout Christian, Yohannes felt the Muslim infidels were a

much greater threat to his empire than were the Italians. His retreat only

encouraged the Italians, who interpreted the withdrawal as a sign of

weakness.

In 1888,

the reinforced Italians reoccupied Saati, constructed a railroad to ferry

supplies from Massawa and fortified the town. Yohannes responded with 80,000

troops and a demand for immediate withdrawal. The Italians, however, held firm

and issued conterdemands which included Ailet, Ghinda and control of the

lowlands. The two armies remained poised on the brink of battle for several

weeks until Yohannes was obliged once again to withdraw to deal with the

Dervishes. Being a devout Christian, Yohannes felt the Muslim infidels were a

much greater threat to his empire than were the Italians. His retreat only

encouraged the Italians, who interpreted the withdrawal as a sign of

weakness.

The railroad reached Asmara by 1920. Photo: Mike Hoffman |

![]() Yohannes

died from battle wounds shortly thereafter and Menelik II acceded the throne.

After Yohannes' death, Ras Alula withdrew his armies into Tigre, and the

Italians took advantage of the Lame Duck government by moving further inland.

By June, 1889, they held Keren, and by August, they had occupied Asmara and

deployed troops along the banks of the Mareb River. Faced with de facto

protectorate. The Amharic version, however, provided that the Emperor merely

had the option of using the Italian Government in that capacity. disagreement

over this clause led to an eventual denunciation of the entire treaty by

Menelik and to rapid deterioration of relations between the two nations.

Implicit in these machinations was the Italian aim of increasing holdings in

East Africa without resorting to force, but once Menelik short-circuited their

plans the only alternative was outright aggression. The famous Battle of Adowa

was the upshot.

Yohannes

died from battle wounds shortly thereafter and Menelik II acceded the throne.

After Yohannes' death, Ras Alula withdrew his armies into Tigre, and the

Italians took advantage of the Lame Duck government by moving further inland.

By June, 1889, they held Keren, and by August, they had occupied Asmara and

deployed troops along the banks of the Mareb River. Faced with de facto

protectorate. The Amharic version, however, provided that the Emperor merely

had the option of using the Italian Government in that capacity. disagreement

over this clause led to an eventual denunciation of the entire treaty by

Menelik and to rapid deterioration of relations between the two nations.

Implicit in these machinations was the Italian aim of increasing holdings in

East Africa without resorting to force, but once Menelik short-circuited their

plans the only alternative was outright aggression. The famous Battle of Adowa

was the upshot.

![]() Menelik's

reign was the foundation of modern Ethiopia. By appeasing the Italians on his

northern borders, he won time to extend his authority into the incorrigible

pagan and Muslim areas of the south. The establishment of Addis Ababa as the

permanent capital in 1893 demonstrated Menelik's interest in the southern

regions. For the first time, the disruptive power of the feudal chiefs was

virtually eliminated, so when the Italians attacked, they met a united Ethiopia

head-on.

Menelik's

reign was the foundation of modern Ethiopia. By appeasing the Italians on his

northern borders, he won time to extend his authority into the incorrigible

pagan and Muslim areas of the south. The establishment of Addis Ababa as the

permanent capital in 1893 demonstrated Menelik's interest in the southern

regions. For the first time, the disruptive power of the feudal chiefs was

virtually eliminated, so when the Italians attacked, they met a united Ethiopia

head-on.

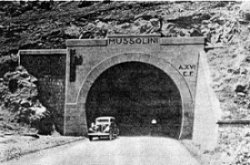

![]() On

January 1, 1890, Umberto I, King of Italy, proclaimed the Colony of Eritrea,

and his army secretly began plans for the invasion of Ethiopia. The invasion

plans were implemented in November, 1895. After losing a few skirmishes near

Makalle, the Italians attached Adowa. In the only battle in which an African

power has defeated a European one, Menelik's armies outfought the Italians in

the three-day battle and drove them back across the Mareb river. It was a great

victory for Menelik and a humiliating defeat for Italy, who lost 12,000

soldiers as well as international prestige. It was the humiliation of Adowa

that Mussolini was determined to avenge when the Fascist armies invaded again

in 1939.

On

January 1, 1890, Umberto I, King of Italy, proclaimed the Colony of Eritrea,

and his army secretly began plans for the invasion of Ethiopia. The invasion

plans were implemented in November, 1895. After losing a few skirmishes near

Makalle, the Italians attached Adowa. In the only battle in which an African

power has defeated a European one, Menelik's armies outfought the Italians in

the three-day battle and drove them back across the Mareb river. It was a great

victory for Menelik and a humiliating defeat for Italy, who lost 12,000

soldiers as well as international prestige. It was the humiliation of Adowa

that Mussolini was determined to avenge when the Fascist armies invaded again

in 1939.

![]() After the

setback at Adowa, Italy temporarily set aside her ambitions and concentrated

energies on organizing the colony. Italy's colonial motives and goals were more

or less the same as those of other countries--to tap the abundant natural

resources for Italian industry, to establish a clearinghouse for Italian

exports and to offer a potential home for expatriate Italian citizens.

Moreover, Eritrea was to become the staging area for further territorial

acquisitions. Invasion plans for Ethiopia. volume two, were finalized in

1934.

After the

setback at Adowa, Italy temporarily set aside her ambitions and concentrated

energies on organizing the colony. Italy's colonial motives and goals were more

or less the same as those of other countries--to tap the abundant natural

resources for Italian industry, to establish a clearinghouse for Italian

exports and to offer a potential home for expatriate Italian citizens.

Moreover, Eritrea was to become the staging area for further territorial

acquisitions. Invasion plans for Ethiopia. volume two, were finalized in

1934.

![]() The early

years of colonial rule in Eritrea were benign, and Eritrea outpaced Ethiopia in

material progress. The Italian administration won popular acceptance by

establishing security in previously dangerous areas, administering equitable

justice, raising the standard of living and developing any number of public

services in the cities, particularly in Asmara and Massawa. The civil governor

ruled from Massawa until 1900 when he moved to Asmara.

The early

years of colonial rule in Eritrea were benign, and Eritrea outpaced Ethiopia in

material progress. The Italian administration won popular acceptance by

establishing security in previously dangerous areas, administering equitable

justice, raising the standard of living and developing any number of public

services in the cities, particularly in Asmara and Massawa. The civil governor

ruled from Massawa until 1900 when he moved to Asmara.

![]() In a

word, the pre-Fascist years in Ethiopia were relaxed. Eritrea moved gradually

toward the 20th century with agricultural reform, road and transportation

systems, medical services and communication. When the Fascists took the reins

of government in Italy, however, the picture changed dramatically. The Fascist

administration in Eritrea imposed strict racial segregation and gave urgent

priority to military preparations throughout the colony. The railroad linking

Massawa, Asmara, Keren and Agordat had been completed in 1920, so road

construction became the primary focus of the military preparations. General de

bono, who was to lead the planned invasion, landed at Massawa January 16, 1935

with 50,000 Italian workers who were to sustain the supply lines. The Italian

army was expanded and Eritrean recruitment increased threefold. Massawa

blossomed into a modern seaport and the Gura Airport was enlarged and

re-equipped. The railroad's major function was military transportation and an

aerial tramway was constructed to expedite movement of material.

In a

word, the pre-Fascist years in Ethiopia were relaxed. Eritrea moved gradually

toward the 20th century with agricultural reform, road and transportation

systems, medical services and communication. When the Fascists took the reins

of government in Italy, however, the picture changed dramatically. The Fascist

administration in Eritrea imposed strict racial segregation and gave urgent

priority to military preparations throughout the colony. The railroad linking

Massawa, Asmara, Keren and Agordat had been completed in 1920, so road

construction became the primary focus of the military preparations. General de

bono, who was to lead the planned invasion, landed at Massawa January 16, 1935

with 50,000 Italian workers who were to sustain the supply lines. The Italian

army was expanded and Eritrean recruitment increased threefold. Massawa

blossomed into a modern seaport and the Gura Airport was enlarged and

re-equipped. The railroad's major function was military transportation and an

aerial tramway was constructed to expedite movement of material.

«None of the 'spontaneous cheers for il Duce had been painted out or defaced by the British...nothing. I thought, so showed British contempt for Mussolini and all he might yet attempt as those uneffaced self-testimonials.» Commander Edward Ellsberg Photo: Robert Hicks |

![]() The

arduous journey from Massawa's docks to Asmara's depots atop the escarpment was

a difficult and time-consuming one on the narrow-gauge railroad. The aerial

ropeway offered a viable alternative for moving supplies quickly from the port.

The ropeway was completed in 1936 and was the longest of its kind in the world.

It reached 44½ miles across the torrid lowlands and scaled the

escarpment stretched between towers up to 3,000 feet apart. Eight diesel power

stations maintained continuous movement for the 1500 3'x5' cargo trams which

delivered 30,000 tons of cargo to Asmara each day. The ropeway was in operation

for only five years. The British liberators took the diesel engines with them

as they left to fight Rommel in North Africa.

The

arduous journey from Massawa's docks to Asmara's depots atop the escarpment was

a difficult and time-consuming one on the narrow-gauge railroad. The aerial

ropeway offered a viable alternative for moving supplies quickly from the port.

The ropeway was completed in 1936 and was the longest of its kind in the world.

It reached 44½ miles across the torrid lowlands and scaled the

escarpment stretched between towers up to 3,000 feet apart. Eight diesel power

stations maintained continuous movement for the 1500 3'x5' cargo trams which

delivered 30,000 tons of cargo to Asmara each day. The ropeway was in operation

for only five years. The British liberators took the diesel engines with them

as they left to fight Rommel in North Africa.

![]() Italy's

ambitions had bene emboldened by the conciliatory posture of the British, and

after fabricating a border incident at Wal Wal, 400,000 armor-supported Italian

troops crossed the Mareb River into the Ethiopian frontier October 3, 1935.

H.I.M. Haile Selassi's 35,000 troops, armed mostly with spears and swords, were

crushed in almost every confrontation, but it the outcome of the battle were

ever in question, mustard gas quickly tipped the balance. By April, the

invading Italians had reached Lake Tana and Harrar, and the Emperor escaped

into exile through Djibouti. Addis Ababa fell in May, and Italy announced the

sovereignty of Italian East Africa (comprised of Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia)

shortly thereafter.

Italy's

ambitions had bene emboldened by the conciliatory posture of the British, and

after fabricating a border incident at Wal Wal, 400,000 armor-supported Italian

troops crossed the Mareb River into the Ethiopian frontier October 3, 1935.

H.I.M. Haile Selassi's 35,000 troops, armed mostly with spears and swords, were

crushed in almost every confrontation, but it the outcome of the battle were

ever in question, mustard gas quickly tipped the balance. By April, the

invading Italians had reached Lake Tana and Harrar, and the Emperor escaped

into exile through Djibouti. Addis Ababa fell in May, and Italy announced the

sovereignty of Italian East Africa (comprised of Eritrea, Ethiopia and Somalia)

shortly thereafter.

![]() Fulminating again from his balcony over the Piazza Venezia,

Mussolini vowed a humiliating defeat for the British in the Middle East as a

partial restoration of the glories of the Roman Empire. Italy declared war on

Great Britain and France June 10, 1940. The same day, the Italian army poured

into France. In Africa, Italy attacked Sudan and Egypt. Fearing the

vulnerability of extended supply lines, the Italian armies remained in the

border regions of Kassala and Gallabat, thereby giving the British ample time

to marshall their meager forces. In the face of stiffening British resistance,

the Italian army retreated to a more defensible position. After being defeated

at Agordat in February, they retreated to Keren where they were again

overwhelmed in a spectacular two-month battle. After a few more skirmishes, the

Italians surrendered. Asmara and Massawa, barely ten months after declaring war

on Britain.

Fulminating again from his balcony over the Piazza Venezia,

Mussolini vowed a humiliating defeat for the British in the Middle East as a

partial restoration of the glories of the Roman Empire. Italy declared war on

Great Britain and France June 10, 1940. The same day, the Italian army poured

into France. In Africa, Italy attacked Sudan and Egypt. Fearing the

vulnerability of extended supply lines, the Italian armies remained in the

border regions of Kassala and Gallabat, thereby giving the British ample time

to marshall their meager forces. In the face of stiffening British resistance,

the Italian army retreated to a more defensible position. After being defeated

at Agordat in February, they retreated to Keren where they were again

overwhelmed in a spectacular two-month battle. After a few more skirmishes, the

Italians surrendered. Asmara and Massawa, barely ten months after declaring war

on Britain.

![]() The

more-or-less takeover by the British found them ill-equipped to cope with the

problems of administering their newly-won territory. The minuscule

administrative staff faced a number of exigent problems. The 50,000 Italian

residents were generally intractable and fully expected immediate liberation

from British dominance. General economic upheaval became widespread as local

Italian industry ground to a halt. The British administration embarked on a

moderate course of action to win popular support. They fortified this position

with relief funds and philanthropic enterprise. The success of this transition

period is owing in part to the fact that many of the Italian officials remained

at their jobs and supported the British.

The

more-or-less takeover by the British found them ill-equipped to cope with the

problems of administering their newly-won territory. The minuscule

administrative staff faced a number of exigent problems. The 50,000 Italian

residents were generally intractable and fully expected immediate liberation

from British dominance. General economic upheaval became widespread as local

Italian industry ground to a halt. The British administration embarked on a

moderate course of action to win popular support. They fortified this position

with relief funds and philanthropic enterprise. The success of this transition

period is owing in part to the fact that many of the Italian officials remained

at their jobs and supported the British.

![]() Any

grandiose plans the British may have had for Eritrea were frustrated by

provisions of the Hague Convention which forbad occupying powers during wartime

to change laws and institutions within any occupied country. The British,

however, did manage to abrogate segregation by simply not enforcing the Fascist

laws, and at the same time, instituted a variety of programs to bolster the

morale and vivify the economy. They gradually integrated Eritreans into the

civil service infrastructure and focused attention on the inadequate

educational facilities. They established the first teacher training institute

and converted wartime buildings into schools and hospitals.

Any

grandiose plans the British may have had for Eritrea were frustrated by

provisions of the Hague Convention which forbad occupying powers during wartime

to change laws and institutions within any occupied country. The British,

however, did manage to abrogate segregation by simply not enforcing the Fascist

laws, and at the same time, instituted a variety of programs to bolster the

morale and vivify the economy. They gradually integrated Eritreans into the

civil service infrastructure and focused attention on the inadequate

educational facilities. They established the first teacher training institute

and converted wartime buildings into schools and hospitals.

![]() The end

of Italian dominance spelled the virtual collapse of the Eritrean economy.

Since all exports went to Italy, Eritrea had become wholly dependent on the

Italian economy. All Eritrean industry had been managed by Italians and

equipped with Italian machinery. Since the small-scale industries and the vast

military preparations in Eritrea had relied on an Eritrean labor force, Italian

defeat meant widespread unemployment. To assuage the unemployment problem, the

British repatriated many of the Italians and shipped POW's to Kenya, South

Africa and India. American intervention into the war in 1941, and intervention

into Eritrea shortly thereafter, bolstered the economy for a while, but with

the Allied victory in the Middle East, it slumped once again. The British

Administration encouraged new Eritrean-owned industry and agricultural

development to absorb the labor force, but the next few years were trying ones,

and the economy vacillated.

The end

of Italian dominance spelled the virtual collapse of the Eritrean economy.

Since all exports went to Italy, Eritrea had become wholly dependent on the

Italian economy. All Eritrean industry had been managed by Italians and

equipped with Italian machinery. Since the small-scale industries and the vast

military preparations in Eritrea had relied on an Eritrean labor force, Italian

defeat meant widespread unemployment. To assuage the unemployment problem, the

British repatriated many of the Italians and shipped POW's to Kenya, South

Africa and India. American intervention into the war in 1941, and intervention

into Eritrea shortly thereafter, bolstered the economy for a while, but with

the Allied victory in the Middle East, it slumped once again. The British

Administration encouraged new Eritrean-owned industry and agricultural

development to absorb the labor force, but the next few years were trying ones,

and the economy vacillated.

After the surrender of all Italian forces in Eritrea, the prisoners of war were interned in camps or «labor pools». Some of them became employees of the U.S. Naval Repair Base, Massawa, some were transported to labor camps in South Africa and others worked on the various American construction projects in Eritrea. |

![]() At the

end of the war, the Allies began ridding themselves of former Axis-occupied

territories. Eritrea posed a formidable problem because of the cogent claims

made by Ethiopia and Italy. After many months of quibbling and two ineffectual

fact-finding commissions in Eritrea, the General Assembly of the United Nations

voted on December 2, 1950 that Eritrea should become federated with Ethiopia.

The decision was influenced by the majority of Eritrean Christians who favored

federations, as well as by the geographical and ethnic affinity of the two

countries. The relationship between Eritrea and Ethiopia was to be similar to

the relationship between state and federal governments of the United States.

Eritrea was to have internal self-government while under the sovereignty of the

Emperor. September 15, 1952 was set for the beginning of the federation, a date

which allowed time for a government to be established and a constitution

promulgated. A Bolivian diplomat was given the responsibility of drafting a

constitution with the assistance of the British in-country administration.

At the

end of the war, the Allies began ridding themselves of former Axis-occupied

territories. Eritrea posed a formidable problem because of the cogent claims

made by Ethiopia and Italy. After many months of quibbling and two ineffectual

fact-finding commissions in Eritrea, the General Assembly of the United Nations

voted on December 2, 1950 that Eritrea should become federated with Ethiopia.

The decision was influenced by the majority of Eritrean Christians who favored

federations, as well as by the geographical and ethnic affinity of the two

countries. The relationship between Eritrea and Ethiopia was to be similar to

the relationship between state and federal governments of the United States.

Eritrea was to have internal self-government while under the sovereignty of the

Emperor. September 15, 1952 was set for the beginning of the federation, a date

which allowed time for a government to be established and a constitution

promulgated. A Bolivian diplomat was given the responsibility of drafting a

constitution with the assistance of the British in-country administration.

![]() The

period just prior to federation was perhaps the most difficult for the British

Administration. Problems arising from land claims and religious controversy

were exacerbated by unemployment and aroused political feelings. The upshot was

an acute shitfa problem which subsumed simple banditry as well as armed

confrontations between the Christian and Muslim factions of the society. The

offer of a general amnesty in June, 1951 served to ameliorate the problem and

put an end to the fighting. Once tranquility was restored to the countryside,

the transfer of authority to the fledgling Eritrean government became the final

objective of the British caretakers. The United Nations resolution took effect

September 11, 1952.

The

period just prior to federation was perhaps the most difficult for the British

Administration. Problems arising from land claims and religious controversy

were exacerbated by unemployment and aroused political feelings. The upshot was

an acute shitfa problem which subsumed simple banditry as well as armed

confrontations between the Christian and Muslim factions of the society. The

offer of a general amnesty in June, 1951 served to ameliorate the problem and

put an end to the fighting. Once tranquility was restored to the countryside,

the transfer of authority to the fledgling Eritrean government became the final

objective of the British caretakers. The United Nations resolution took effect

September 11, 1952.

![]() The

federation was unsuccessful, mostly because of Ethiopia's resentment of

Eritrea's semi-autonomous status. Ethiopia feared Eritrea might serve as an

undesirable encouragement for separatist sentiments in other areas. The

Eritrean Parliament succumbed to political pressure and dissolved itself in

November, 1962, and Eritrea became the Empire's fourteenth province.

The

federation was unsuccessful, mostly because of Ethiopia's resentment of

Eritrea's semi-autonomous status. Ethiopia feared Eritrea might serve as an

undesirable encouragement for separatist sentiments in other areas. The

Eritrean Parliament succumbed to political pressure and dissolved itself in

November, 1962, and Eritrea became the Empire's fourteenth province.

Historically, shifta chicanery has often taken on political

overtones, but the brigands who happened on these two Asmara gentlemen were

interested in more substantial returns. The shifta took everything they could

carry or wear. The remaining set of clothing was rejected disdainfully as being

ragged and unserviceable. Historically, shifta chicanery has often taken on political

overtones, but the brigands who happened on these two Asmara gentlemen were

interested in more substantial returns. The shifta took everything they could

carry or wear. The remaining set of clothing was rejected disdainfully as being

ragged and unserviceable.Photo: Charles Krumbein |