Ethiopia

A Hidden Empire of ecclesiastical

and Secular

Treasures

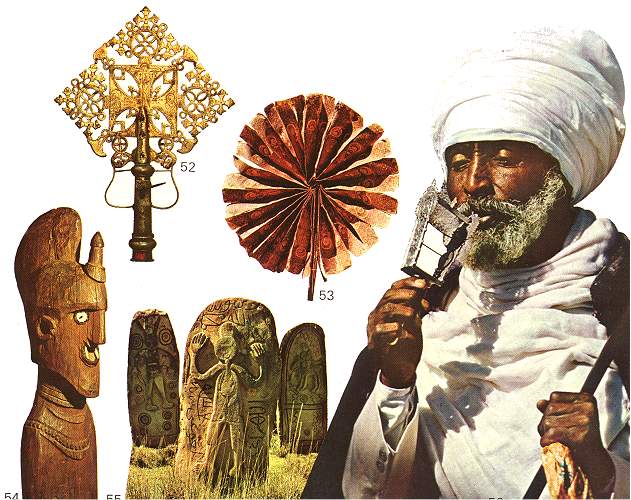

But the churches that can be visited, and they are multitudinous, suffice to give an impressive insight into the faith and inspiration of Ethiopia's kings, architects and artists. Priests in their rich, colourful vestments will spend patient hours proudly displaying their vast treasures of religious and secular objects, their heritage of vestments and beautifully-illuminated missals, their ceremonial crosses and musical instruments.

Endearingly attractive are the "story pictures" of Ethiopia: brightly-coloured graphic representations of scenes from the Bible and from the country's history. And not the least of their charms is the knowledge that those you can purchase in the market today are executed in exactly the same technique as has been used for over 2,000 years-indeed, only by the type of paint and the material on which they are painted (and their price!) carfyou be sure whether your purchase dates from more than 20 centuries ago, or from the day before yesterday. You find them everywhere, on the walls and ceilings of tiny, tucked-away shrines and monas=teries; in larger churches and abbeys; in private homes; and in the markets everywhere. Painted on canvas, on leather, on parchment, on any surface that will hold paint, they bear witness to an abiding faith combined with a lively sense of the dramatic and, occasionally, deep flashes of humour.

Wood-carving, too, has been an Ethiopian craft for centuries: ceilings, walls, lintels, doors, are finely carved and decorated, often with flowers, trees and beasts. The humblest village musician will proudly show you his home-made musical instrument, lovingly and patiently carved, often surmounted by a cross.

The crosses of Ethiopia in themselves are worth hours of study. They exist in infinite variety, both of design

Secular treasures, too, abound. Jewel-studded crowns and diadems; ruby and emerald-encrusted -daggers and shields; silver birelas, the vessels that hold tej Ethiopia's honey wine; rich, brocaded robes; splendidly-worked goblets and table-ware.

The Ethiopian has a keen sense of beauty and design, from the nomad girl, patiently plaiting a fresh wreath of leaves to encircle her forehead, to the priest bent over the parchment missal he is illuminating in accordance with an ageold tradition. Forthe visitor, the fruits of their labour over the centuries, is a rich harvest of interest and beauty.